hpo economic commentary, 2nd quarter 2023

What is the situation regarding industrial order intake?

After the corona-related forced breaks of the large industrial trade fairs, numerous international trade fairs could be held again in the last months. The hpo forecasting team visited various trade fairs in the course of spring and was able to hold numerous discussions with decision-makers from the industry. The mood was similar to what Christine Lagarde, President of the European Central Bank, said at the World Economic Forum (WEF) in January: “Not as bad as feared”.

Following the absence of the energy crisis in Europe and the lifting of the strict Corona measures in China, a sense of relief is noticeable among decision-makers in the industry. Sales remain at an encouraging level due to the still very high order backlog and the normalisation of the supply chain situation. The German Engineering Federation (VDMA) recently reported that its members are currently reporting an average order backlog that will allow them to operate at capacity for almost 12 months. This cushion is a positive sign.

Share article

What is often forgotten when interpreting companies’ quarterly figures is the fact that companies always communicate nominal growth figures. In recent decades, this has never been a problem, as inflation rates have always been very low. But with the current inflation figures of 7 % in the Eurozone, constant order intake figures actually mean a painful decline.

Taking the order intake of German mechanical engineering companies as an example, the situation is as follows: In the first quarter of 2023, order intake increased by 3.5 % compared with the final quarter of 2022. This means that the order intake of German mechanical engineering companies was recently only 2.5 % below the previous record quarter Q1 2021 in nominal terms.

In real terms, the positive picture is put into perspective, as inflation-adjusted order intake fell by a whopping 10.5 % year-on-year in Q1 2023 according to Destatis data.

In the USA, too, order intake by mechanical engineering companies fell by only 2.6 % year-on-year in nominal terms. However, in real terms this also corresponds to a considerable decline there. The forecast decline in industrial order intake is already a fact in most industry segments, but is not perceived as such in many cases due to the high nominal values.

Order intake of German mechanical engineering companies – real and nominal

Raw data by Destatis, illustration by hpo forecasting

Automotive catches up

Following the pandemic shock in the first half of 2020, the industry benefited from extremely strong demand across the board. As has been repeatedly stated here, this boom was driven by the unprecedented stimulus measures taken by governments, particularly in the USA. Somewhat strikingly, the context can be summarised as follows: The Americans stimulated consumption with very high transfer payments to the population, and the great demand for consumer goods was satisfied by Chinese producers, who procured numerous machines from Europe for this purpose. The exploding American demand for consumer goods and the digitalisation push caused demand for semiconductors to skyrocket and led to delivery problems, from which the automotive industry in particular suffered greatly.

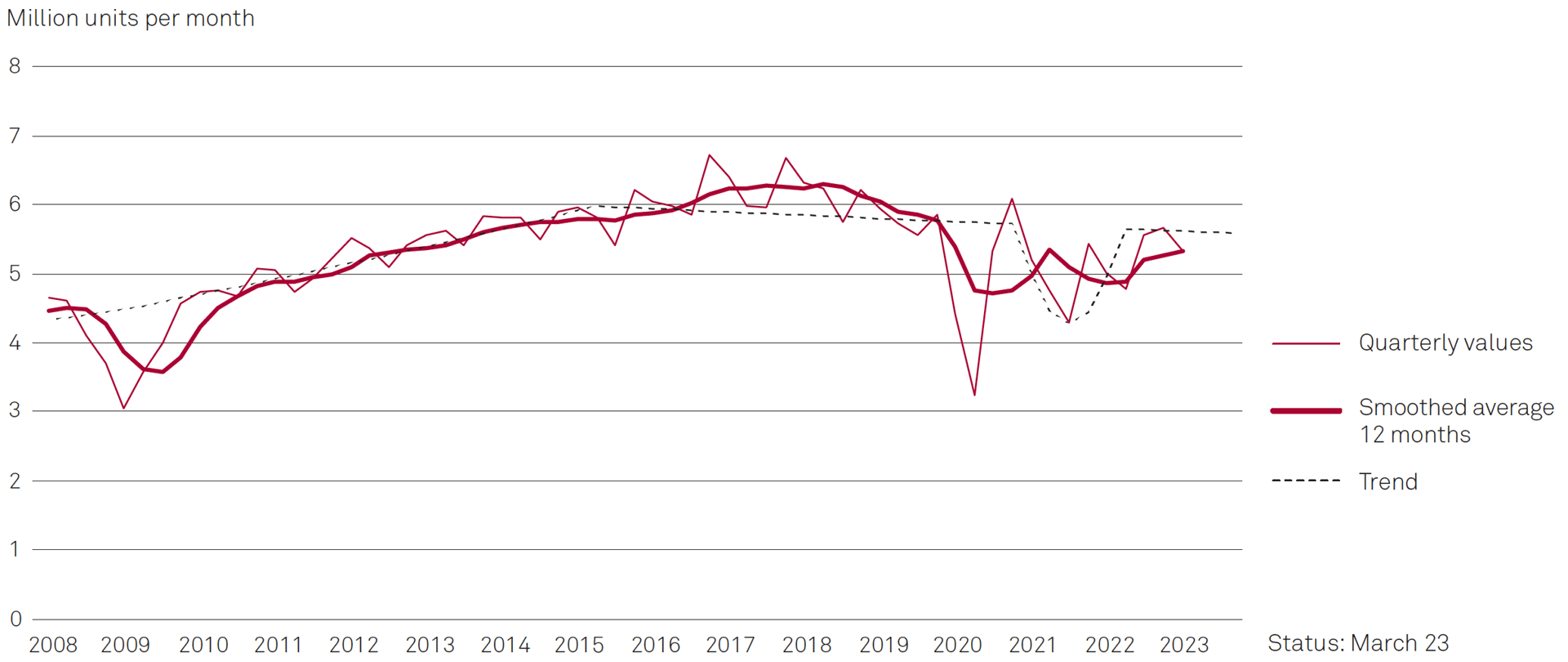

The loser in this dynamic was the automotive industry. According to hpo model calculations, the number of newly registered automobiles in the USA, for example, remained at a level around 20 % lower between mid-2021 and Q3 2022 than could have been expected on the basis of economic indicators. The same applies to global automotive production. This phase now seems to be slowly coming to an end, and a clear upward trend can be seen in both new car registrations and their production. However, it is questionable whether the underconsumption of vehicles from mid-2021 onwards can now be compensated for by overconsumption, as the easing on the production side now coincides precisely with a period in which a cyclically induced fall in demand must again be expected. Our expectation is therefore that, despite catch-up effects, the previous record levels of global vehicle production seen in 2018 will not be matched for the time being. This is aggravated by the fact that trend growth in global automotive production has already been slightly negative since 2015.

Monthly car production of the most important car manufacturers, which together account for approx. 88 % of global production

Source: raw data by Trading Economics, illustration by hpo forecasting

Consumers in a bad mood are still in a spending mood

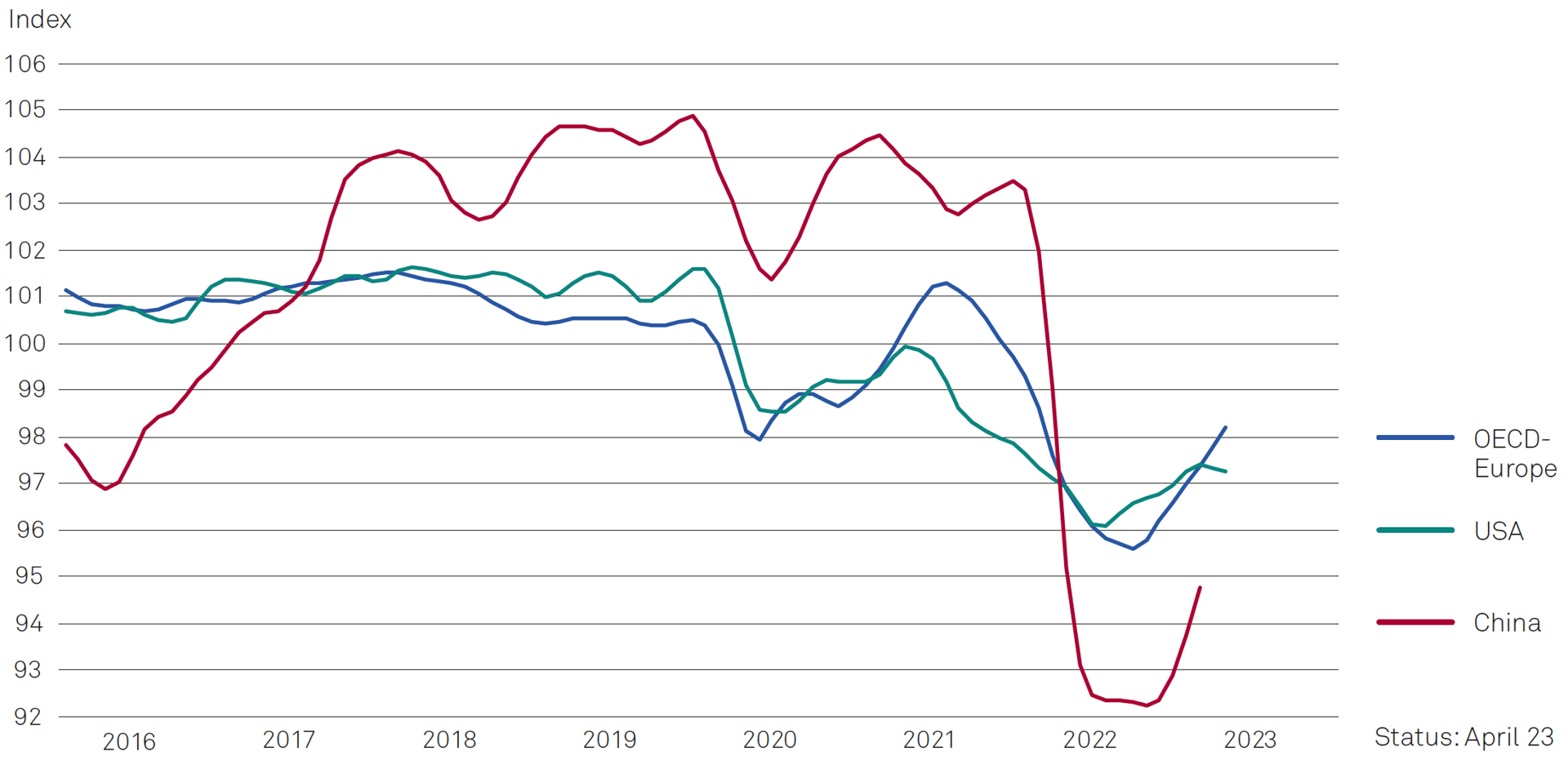

Buoyant consumer spending remains a key pillar of the good economic situation. This is despite the fact that consumer sentiment in 2022 was the lowest ever recorded not only in the USA, but also in Europe and China. This is astonishing, as unemployment rates in Europe and the USA were very low and job security high at the same time. However, the pandemic, the Ukraine crisis and high inflation are causing great uncertainty. In the meantime, the troughs have clearly been passed, but consumer sentiment remains deep in contractionary territory. In the USA, sentiment has recently fallen again slightly after a recovery phase of three quarters and currently stands at 97.3 points, still below the low level of spring 2020, the peak of the corona crisis in America.

Consumer Confidence Index (CCI)

Source: raw data by OECD, illustration by hpo forecasting

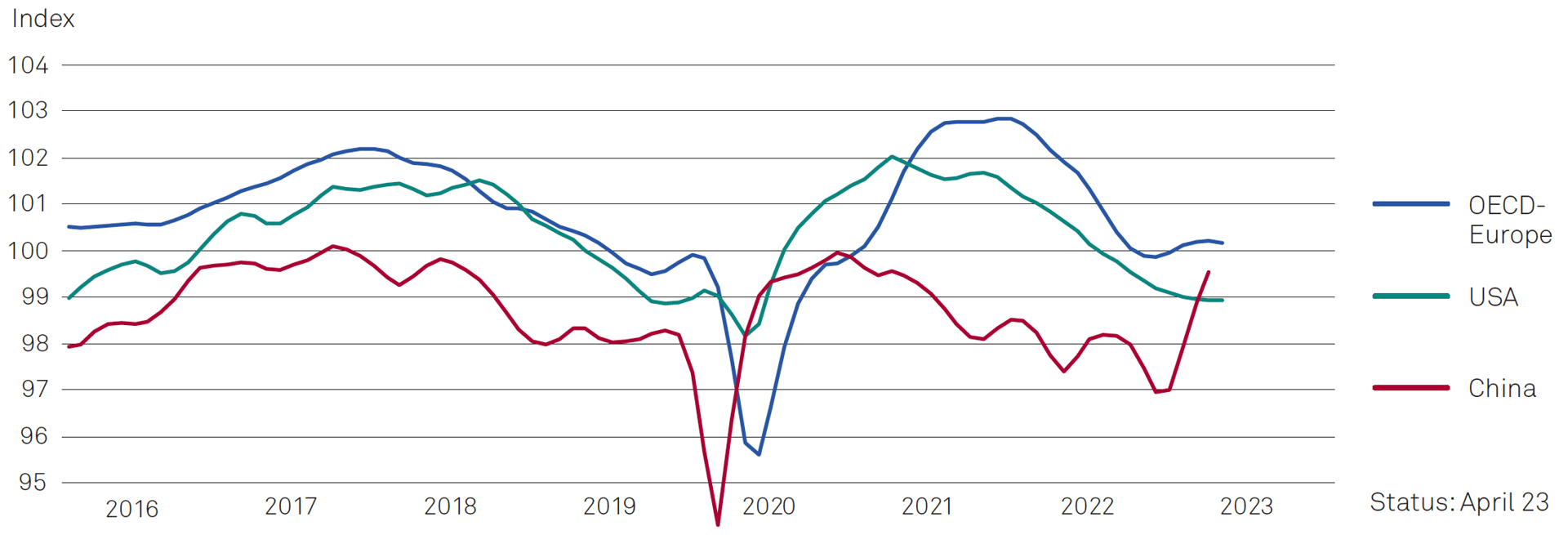

The domestic-oriented sectors in particular are benefiting from the upturn in sentiment in China

The mood among companies continues to be markedly better. In China, the Business Confidence Index (BCI) published by the OECD rose from its low in November (96.9 points) to almost 99.5 points in May, just below the neutral value of 100 points. However, contrary to analysts’ expectations, the Purchasing Managers’ Index of the manufacturing sector (Manufacturing PMI) surveyed by the Chinese economic journal Caixin fell back just into contractionary territory in April after two months in expansionary territory. The rapidly improving sentiment in China is mainly driven by the domestically oriented service sector, while exports from China have declined markedly since the end of 2022.

In Europe, the BCI is moving in neutral territory just above 100, recently with a slight downward trend again.

In the USA, economic sentiment is somewhat more pessimistic and in April the BCI stood at just under 99 points. The wave of bankruptcies among American regional banks is likely to depress sentiment here. Various analysts point out that regional banks have a dominant market position as lenders to medium-sized companies. Due to the major liquidity difficulties of the regional banks, the financing conditions for these SMEs have suddenly deteriorated. This will result in financing difficulties and further depress sentiment among small and medium-sized enterprises. This also includes many industrial companies.

Business Confidence Index (BCI)

Sources: raw data by OECD, illustration by hpo forecasting

Overall, hpo’s model calculations show falling order intake figures for industry in the coming quarters and a general slowdown in economic momentum.

High government debt back in focus worldwide

In times of ultra-low interest rates, the issue of high government debt was pushed somewhat into the background. However, following the sharp hikes in key interest rates since the beginning of 2022, the cost of debt has risen sharply. This is all the more significant because government spending exploded, especially during the pandemic. For example, over the past two years in the United States, federal government debt increased by about a third to more than USD 31 trillion, reaching 117 % of gross domestic product.

Development of government debt (national level only) in the United States, China and the euro area as a percentage of GDP

Source: raw data by Bank for International Settlements (BIS), illustration by hpo forecasting

The high level of public debt in all major economic regions is increasingly becoming a problem and threatens to drag down the economy in both the short and long term.

In the short term, the greatest risk of economic dislocation is in the United States. In the United States, the federal government’s debt ceiling is set by law and currently stands at USD 31.4 trillion. This limit has been reached in the interim and default can only be prevented with sophisticated liquidity management and tapping of reserves. In Congress, the Democrats need the consent of at least part of the Republicans to raise the debt ceiling. In exchange for their concession, however, the Republicans are demanding massive cost reductions in the Democrats’ pet projects in the areas of climate and social security. That, in turn, is unacceptable to the Democrats. If the two parties cannot reach an agreement in the coming weeks, the U.S. government will be threatened with insolvency in June. This has happened repeatedly before (most recently before the pandemic during Donald Trump’s presidency), and it has always happened without too much economic collateral damage because the parties eventually reached an agreement.

Unlike in the past, however, the U.S. economy is in much more fragile shape today, and many economists expect a mild recession in the course of the year anyway. The banking system has been suffering stress for months. Misjudgments by the parties in the negotiation poker could have disastrous consequences in this environment, warned Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen in early May. Core inflation remains well above 5 % in Europe and the USA. The fight against inflation so far has been relatively easy because central banks have been able to raise key interest rates in a strong economic environment. However, there is still a long way to go to achieve price stability, and if the economy cools down as expected, the pressure on central banks to take their foot off the brake pedal will increase.

As key interest rates rise, so do the costs of servicing public debt. The European Central Bank (ECB) has only been able to implement its interest rate hikes since last summer thanks to the simultaneous introduction of a new instrument. This allows it to buy government bonds of heavily indebted euro states on a large scale. It prevented the risk premiums for highly indebted countries from rising sharply. Without this instrument, the current key interest rate increases would hardly have been possible without a simultaneous euro crisis. The consideration for the over-indebted European countries hinders the ECB in its fight against inflation.

In China, too, debt has risen very sharply, particularly since the financial crisis, especially that of the regional governments. These were urged to invest heavily in infrastructure in order to achieve the ambitious growth targets. According to reports in the business magazines Caixin and The Economist, Guizhou province is close to insolvency, and other provinces are in a similar situation. The American financial theorist Michael Pettis sees the reason for this in the fact that China has the world’s highest investment share of GDP, at 42 % to 44 %. Globally, this share is around 25 %, and in mature economies it is around 15 to 20 % of GDP. Even for emerging economies in the middle of a growth phase, 35 % is a very high figure.

The consequence is that in China today, the economic costs of infrastructure investments are higher than their overall economic benefits. In his extremely readable essay “Can China grow more than 2 to 3 % in the long term?” of April 21, 2023 in the business magazine The Market/NZZ, Pettis convincingly argues that the exploding debt in the country can only be stopped by rebalancing the economy. Or, to put it another way, consumption must increase massively at the expense of infrastructure spending.

If the crushing overweighting of infrastructure spending remains, debt will continue to rise rapidly and massively, and this in a rapidly aging society. Such rebalancing processes, which always involve high adjustment costs, have been experienced by all mature economies throughout history. Depending on how fast the adjustment succeeds, a severe recession or a prolonged period of low economic growth is the side effect.

The first signs of this process are already visible in China with the smoldering real estate crisis. If this development continues, China will face years of low economic growth, and even a recession cannot be ruled out. Companies that are heavily dependent on investments would have to suffer in this scenario. As the share of consumption in GDP must grow significantly in this rebalancing, opportunities are most likely to arise in China for manufacturers of consumer goods and consumer-related sectors.

How robust is the economy in 2023?

How long will the coming crisis last?

Has the peak of demand in the industry already passed?